Reforesting with Indigenous nations

Some of the most successful regeneration projects in the world are led by Indigenous people. Many Indigenous groups have special, even spiritual relationships with certain tree species, and their traditional knowledge can rapidly regenerate ancestral lands.

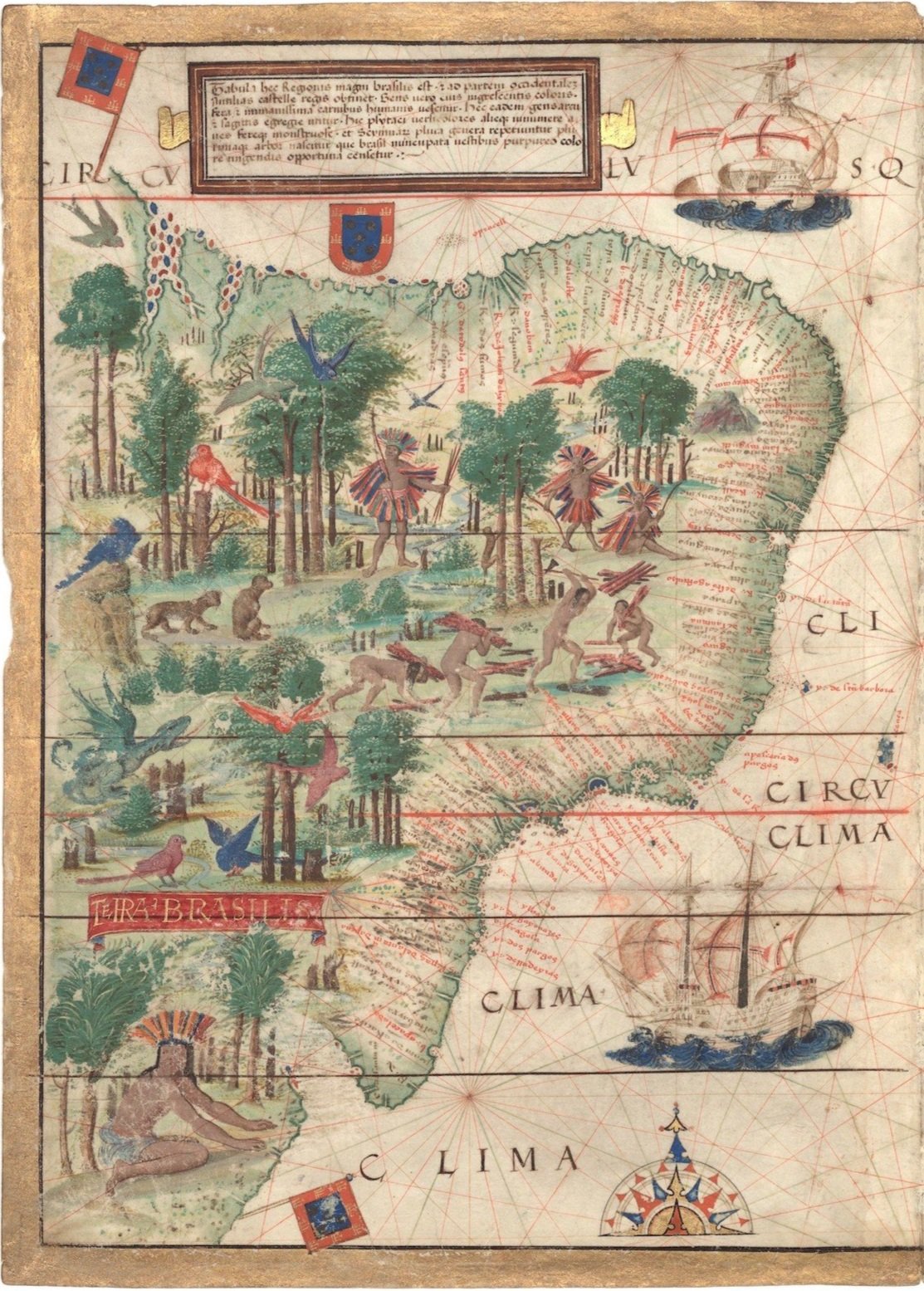

When Europeans first arrived, the enormous landmass of Brazil was predominantly covered with forests. Unlike the cattle-rearing and farming cultures that displaced them, Indigenous people increased the biodiversity of their land using techniques developed over thousands of years of living in harmony with the forest.

The Kaingang culture and the Parana pine

For the Kaingang, the Parana pine (Araucaria angustifolia) plays a central role in their most sacred ceremonies. It is used to demarcate territories, to map routes between different communities. The abundant pine seeds it produces are a rich source of food for many animals, and the Kaingang have worked with the Parana pine forests over time to attract and feed an abundant supply of game animals. In their diaries, early explorers sometimes comment that they have wandered into an area of astonishingly abundant game. These hunters were unaware that the landscape had been managed for centuries by cultures like the Kaingang.

The Parana pine plays a key role in restoring the lost forests of southern Brazil; it is the principle species and acts as a ‘backbone’ for further biodiversity and regeneration to occur. The animals attracted to the pine nuts bring in seeds of other species that they’ve eaten, and new trees grow in their wake.

The pine does not naturally grow from nuts that fall on the ground; they must be buried to germinate, and the Kaingang have been doing this for many centuries. Different clans have also selected and propagated trees over the centuries that flower and fruit in different months, resulting in a range of strains that produce nuts at different times of the year. This means that the tribe has pine nuts for six months of the year, and so do the animals there, making it the ideal regenerative species.

Sadly, the Parana pine is critically endangered today. This tree, that once fed the dinosaurs and covered huge swathes of the planet has retreated to only cover a small area - the Kaingang reserve. Their resistance to the farms and ranches of colonial culture has been instrumental in ensuring its survival until today.

Colonialism in the 21st century

Mature Parana pine

We tend to think of the excesses of colonialism as something in the distant past, but this tree was one of the main sources of material used to rebuild Europe after World War II. Between 1930 and 1990 an estimated 100 million Parana pine trees were felled and exported from the Atlantic forest - much of it from Kaingang territory. European history is intertwined with the tragedy of deforestation that has pushed this culture and this tree to the brink of extinction.

Accepting cultural culpability is not the same as being paralysed by guilt. Non-Indigenous communities have an opportunity to do what must be done to make sure that we associate better with the Indigenous world in the future. The Kaingang have a fantastic project ready to go, and a workforce dedicated to replanting their territories with the Parana pine and other species that can give them autonomy, economic security and resilience in uncertain times.

Working with Indigenous partners

Storyboarding the process of a partnership

RAIN is developing projects in the Indigenous world, finding ways to overcome barriers to communication and the trauma that exists between our cultures, including using a storyboard designed by a Marvel films illustrator to describe the process of our partnership.

School twinning project

Our project with the Terena nation is already producing saplings. The Terena culture used to occupy tens of thousands of hectares, but most was taken from them and degraded by cattle farming. The River Buriti, which feeds 13 separate aldeias (indigenous villages) in the Buriti indigenous reserve, has suffered terribly, and the water volume is dropping year by year as a result. It is the thin green line you can see in the top right of the reserve.

In recent years this nation won back a fraction of their ancestral territory. They have 2090 hectares, 800 of which are highly degraded, and ready to be reforested.

RAIN is working with two Terena nation schools to establish a twinning project with schools in the UK, sharing worldviews, cultural wisdom and regeneration stories.